Is Object Im-permanence Also a Developmental Stage?

On letting our parents die, literally *and* psychologically

If you’ve ever been around a child during their development — or even a dog for that matter — you probably know about object permanence. It’s that developmental achievement where a child understands that even if an object or a person isn’t here at the moment, they continue to exist. Your friend just borrowed your toy, they’ll bring it back. Your mom’s just at work now, she is coming home later. And so on.

But when it comes to death, the opposite is true. I’m not sure developmental psychology has worked out that accepting this, too, is a milestone. The canon on mourning ala Freud, and psychotherapies informed by Buddhism, certainly do. As long as there has been death, we humans have been telling ourselves stories about where people go when they die to help comprehend that this time, they aren’t coming back. In mourning, we work out ways to go on living when the people who set our worlds in motion don’t.

I know a number of people whose parents, in-laws, or grandparents are at the end of their lives presently. They are all on my mind as I write these words, but they are not the primary reason for my writing. Mourning involves those who die literal deaths, and also psychological ones.

A lie slipped out of my mouth the other day when I was explaining my disheveled state to a stranger: “I’m so sorry, I’m not usually like this… but my mom just died.” I shocked myself. I’d never said anything like that before, and my mom was very much still alive. But it was, as Picasso is famous for saying, a lie that revealed the truth.

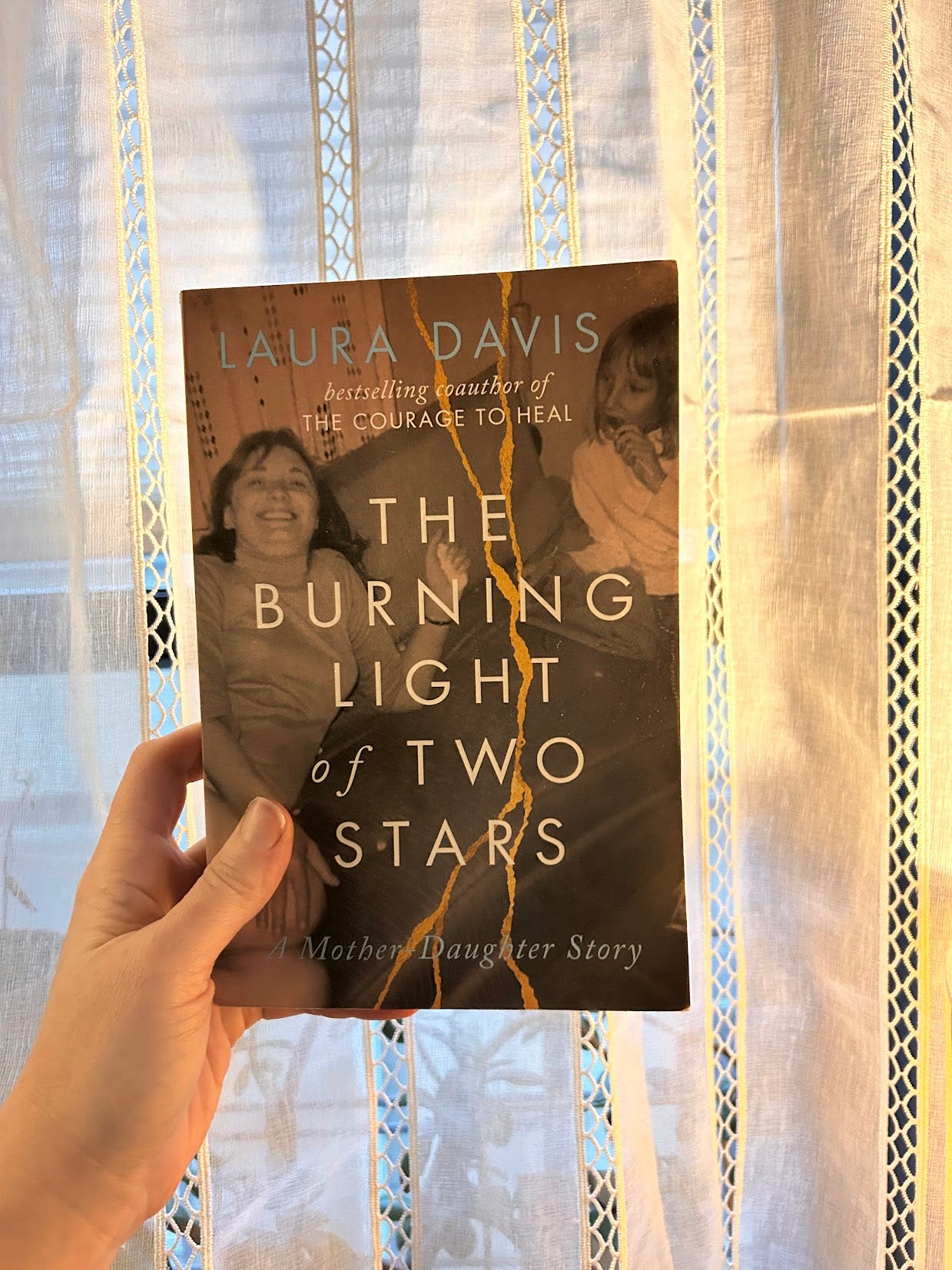

I was in the middle of reading The Burning Light of Two Stars: A Mother-Daughter Story. It’s written by Laura Davis, one of the authors of The Courage to Heal which, in the late 1980’s, helped raise awareness about childhood sexual abuse and the long road of recovering unwanted memories and healing. That book found its way not only to the center of the Recovered Memory Movement, but also to its attackers. Davis writes, in her latest book, that her mother was one of the people who denied her experience of family sexual abuse. Her mother was one of her betrayers. I identified with that.

There are a few things that I didn’t know about this book at first glance though. The first thing is that Davis and her mother had previously collaborated on another book together, called I Thought We’d Never Speak Again: The Road from Estrangement to Reconciliation. It tells their story of loving each other after feelings of mutual betrayal, as well as stories of reconciliation between war criminals and victims and other estranged family members. Davis helpfully identifies that there are different potentials for reconciliation depending on the particularities of each relationship. Not all relationships should be treated as capable of repair, even when repair is of utmost value. More on this later. The second thing I didn’t realize at the outset of reading The Burning Light of Two Stars is that it is a book about her mother’s dying.

This is a remarkable, honest testament to the thread between living and dying; how much care can go into being present for another at the bookends of life; and the great labor it takes to die. (She’s blessedly honest with risky things like the urge to abuse her vulnerable mother out of pent-up frustration and a wish for revenge). I highly recommend it for anyone accompanying another at the end of their life.

Davis writes about attachment and letting go of a parent too: “From the moment she’d stood outside my isolette and pulled me into the world, Mom had always been at the center. At the center of my love. At the center of my hate. At the center of my feigned indifference. I had never stopped revolving around her. I had never escaped her gravitational pull. Now suddenly, I had been released from orbit and was hurtling through space alone. Nothing tethered me to the earth anymore.”

Gravity is perhaps the best analogy there is for attachment. Attachment holds us down and gives us a sense of permanence. That gravitational pull — at least as a constant, predictable force — is something that people with disorganized, insecure attachment styles are lacking in. People like myself.

After a period of early estrangement from my mother, we both had a desire to reunite. Her mother had just died, and even though they had cut off contact for many years leading up to that point, my mother became her end-of-life caregiver. She didn’t want us to be estranged the way they were. My first marriage was ending, and I harbored some wish that a return to my mother’s arms was possible. We had some questions for each other and agreed to ask, listen, and answer. At some point, she told me that throughout her life, her own mother forgot when her birthday was. She didn’t just forget to give her presents; the woman who birthed my mother literally forgot when it happened. I understand now that this was a protective dissociation on the part of her mother, and a damaging one for mine.

I then asked my mother about our birth story. After assuring me that it was not a spiritual experience, she simply said, “Well, I was there.” We both knew intellectually that my body came from hers, but the most my mother could offer was that we were in the same room at the moment of my birth.

I have never known the gravitational pull toward a mother that Davis speaks of. To my children, yes; not to my mother or hers before her. There have been times where we both tried to fix that, but that was before the betrayal.

When I began to remember and speak about my childhood history of abuse, my mother denied it. She pushed hard against me. At the same time, she fiercely defended my father. There were clues all along that this would happen if I ever spoke of abuse, but something broke with an unimaginable finality when I actually did.

As Davis says, “You can’t be absolutely certain of the outcome of a relationship until both people are dead.” It seems to me that this is quite true. Every day a person is alive, there remains the possibility of new affects, revelations, breath, and cells to pass through and transform them.

Along the way, we would do well to be clear-sighted and intentional about the current state of any relationship. Even though repair is the highest ideal — indeed, repair is something that relational psychoanalysis models itself on and works toward — it is essential to recognize that not every relationship is capable of repair. And even in those relationships that are, that may not be true for many phases of the relationship. Sometimes the most important thing is to manage a relationship with firmer boundaries and distance rather than try to repair. This is especially true in instances where permeability would oppress some nascent part of the self. False repair makes one feel good at the expense of the other. It forecloses on life.

When the relationships that cannot be repaired are with our parents, our in-laws, our grandparents — our ancestors — we have the choice to mourn who they have been to us so that we can begin to live differently. They are the ones who made the world for us. Tangibly and neurobiologically they laid our foundations. They taught us language (and didn’t teach us others). They showed us their version of love, of disgust, of what is meaningful and of what is worth putting energy into. But the thing is, they don’t create the whole world. They only ever teach us one version of the world, and at some point that version has to die.

Mourning the ancestors who have betrayed us is a developmental achievement — it allows them to have impermanence in our internal worlds.

But mourning the psychological impact of those who are still living is a thing that, compared to the physical death of a parent, often goes unnoticed. And if it is difficult for others to notice the change, that says something about the mourner herself. It’s easy to push off this mourning. “Nothing’s even happening,” she might say. Or, “This can wait, because other people are going through actual crises right now!” But if we don’t attend to the broken ways our fallible parents have set up our mental worlds for us now, when will we?

This gets to the heart of psychoanalysis. Sometimes we do have to address the immediate happenings in life, but more often, we’re getting at the things that have steadily set in day by day, defining our worlds as if they were ultimate truths. In fact, they ought to be observed, questioned, and occasionally laid to rest.

These inner deaths may even allow us to bring healing to the generations that came before us — like my mother did for her mother. But we can’t rush the process or pretend a relationship is capable in one moment of something it’s not. If some relationship is proving too dangerous to try and repair with, maybe it’s time to shore up your boundaries and let it leave your psychic pantheon. Invite another, more hospitable self to step up. If not now, when?